… PSS are not free baby beds for poor families. They are a central component of a comprehensive service that needs to be embedded into a SUDI prevention strategy and regional infant health plan. A Pēpi-Pod® service needs a project action group, coordinator, PSSs and bedding packs, referral processes and criteria, agencies and distributors authorised to distribute, a thorough recipient briefing, follow-up of and feedback from users, and systems for recording, monitoring, communicating etc.

The Scottish government’s review of student support will be published tomorrow. Once the full report is available, it will be possible to analyse its proposals. This post only considers the spin being put on it today.

Today’s coverage: “best in UK” klaxon

Two papers have been given advance briefing about the report: the Sunday Times and the Sunday Herald (which labels it an “exclusive”).

The headline story in both is that all students in FE and HE will receive £8,100 of living cost support, composed of an unspecified mix of loan and grant which will left to Ministers to decide. A “source” from the review is quoted in both papers as saying

Establishing a minimum student income would be a huge step forward and taken together our recommendations amount to the best student support package that would be available in the UK.

Long time observers of the Scottish Government’s handling of student support announcements will recognise the “best in UK” claim. It was the centrepiece of the SG’s August 2012 announcement, which managed not to mention at all that its plans included a £35m (30%) pa cut in spending in student grants. In 2012, the basis for the favourable comparison was nowhere stated, or teased out by the media at the time. It was nevertheless reported widely: the “best in UK” headline appeared widely across the press unchallenged.

It was digging into this claim out of straightforward curiosity which accidentally set me off towards a new career as a specialist in comparative cross-UK student finance. My conclusion in that earlier work was:

no one system can be claimed as best in the UK, other than subjectively and on the basis of partial comparisons.

This remains true.

So seeing this line was like meeting an old friend. But in a rather surprising context, because this time it is not the SG briefing, but what the SG has officially labelled its “independent review of student support” (emphasis added).

Further, an “exclusive” Sunday briefing before a Monday launch is a longstanding professional PR tactic. Its aim is to manage coverage, by slipping out some conclusions ahead of the rest, accompanied by the preferred interpretation. It means initial reactions are based on imperfect information, selected for maximum favourable impact, plus spin which may go beyond what is actually in the report. It also means that if the full story raises more difficult questions, by the time these emerge, it is old news, editors are more likely to spike coverage and thus criticisms are slightly less likely to get publicity. It was an unexpected tactic for an impartial independent review to adopt.

A partial claim?

“Best in the UK” is a surprising claim for an independent review to fasten on not only because of its resonant and not entirely respectable recent history as a Scottish government spin line, but because it’s unavoidably a subjective claim. There are a broad range of aspects of student funding systems you might compare, including:

- how much students get to live on at the lowest incomes

- how tightly “lowest income” is defined

- how much students get at all other incomes

- how that varies according to whether you live at home or away

- how much of that has to be borrowed

- which categories of students are in and out of scope

- what final debt is at different incomes

- who ends up with the most debt

- the terms of your loan scheme

- etc

There is no scheme which is “best” at all this as of today. The review proposals as revealed so far will not alter that fact.

Most obviously, from next year (the soonest any new Scottish proposals could come in), Welsh students living away from home will be able to claim £9,000 a year (£11,250 in London), £900 more a year than the Scottish review proposes: more here. Moreover, all but £900, ie. £8,100 [NB correction from initial post, which stated the whole amount would be grant] of Welsh living cost support will be provided entirely as non-repayable grant at the lowest incomes, and grant will be worth multiple thousands much further up the income scale, with everyone getting at least £1,000. The Scottish review, we are, told, will leave the Scottish government to choose the grant/loan split. The arrangements in Wales will also cover part-time students pro rata: minutes of review meetings suggest it has only looked at full-timers. In Wales, borrowing is and will remain skewed away from those from the lowest incomes: in Scotland the way is being left open for the opposite to continue. I recently heard the relevant Minister from Wales claiming Wales would have (wait for it) the best system in the UK, even after allowing that students will have to borrow up to £9,000 for fees alongside.

The point is, that claiming to be “best in the UK” means making judgements about what – and who – matters most. If an independent review repeats this claim in its report, it needs to spell out precisely the basis for that claim, and justify why it is ignoring or counting as irrelevant certain areas where it does less well. Otherwise it will sound like no more than the re-run of an old political spin line, which does not belong in this sort of document. And if someone has spun a line ahead of publication which members did not agree to include in the report, that would raise a different question, about who is in control of the review.

Who’s briefing?

It’s in the nature of this sort of story that the source is left vague. The Sunday Herald call him or her “a review group source”. the Sunday Times uses “a source from the review”.

We do know however that the review has engaged Charlotte Street Partners to do at least some of its media work. Invitations to tomorrow’s launch sent to journalists this week came from CSP. CSP is well-known in Scottish lobbying circles: it is one of the most high profile “strategic communications” firms north of the border . Specifically the invitations (or at least the one I’ve seen) are from Kevin Pringle. Pringle’s biography on CSP’s site says:

Kevin Pringle joined us as a Partner in 2015. He is one of our most experienced strategy and communications advisers and has a greater knowledge of Scottish politics than anybody we have ever met. He is widely regarded as one of the most respected strategic communications experts of his generation, having worked in frontline politics for many years, helping steer the SNP successfully from a small opposition party to one of the greatest political success stories of modern times.

Between 2004 and 2006, Kevin earned some valuable private sector experience with Centrica’s Scottish Gas business, before rejoining the SNP’s political machine. Following the 2007 Scottish elections, he was appointed senior special adviser to the first SNP First Minister of Scotland, Alex Salmond. Kevin went on to become director of strategic communications for the SNP, playing a central role in the cross-party Yes campaign. He is currently a columnist for The Sunday Times in Scotland.

From May 2011 until 31 August 2012 Pringle was the SG special adviser in charge of “strategic communications across all portfolios”, so the 2012 “best in UK” line was first developed, as it happens, on his watch in government.

Engaging Pringle to manage its media relations is without doubt therefore an interesting move by the review. Typically these bodies are supported in their activity by officials seconded from government. This one has had a more complex support structure – a mixture of civil servants and staff from Virgin Money (a story for a different day), but invitations to the launch to people like me came from a civil service address. Buying in outside top-end PR help (and as Pringle’s biography shows, you’d struggle go more top end in Scotland than him) specifically to deal with the media is, or used to be, less common for independent advisory bodies. I don’t think it happened with the recent Commission for Widening Access or with the earlier Cubie Review, for example.

Looking past the spin

The real interest in this review will come with access to its full report tomorrow. From the early briefing, the review will not come out arguing unequivocally for extra investment in grant, but offer government a range of choices, which will include using loan to provide all or most extra support. There’ll be plenty to discuss, therefore. Playing games of airy and unexplained one upmanship with other UK nations will, however, be the least interesting way this debate could go, or be covered by the media. Those seriously interested in the substance of policy-making here in Scotland might instead pay particular, careful attention to how decisions that may be made here would affect Scottish students from lower incomes, and what questions this raises for the continued commitment to sinking £1 billion annually in 100% universal cash subsidies for fees (clue: some loan could be deployed here instead, and cash extracted and used for grants).

In August 2012, Mr Pringle and/or his colleagues successfully obscured substantial grant cuts and debt increases for tens of thousands of students from lower income homes by offering a comfort blanket story of national superiority. Let’s make the PR people work a bit harder for their money this time.

Footnote: But … free tuition?

Some people will always feel that any system which is based on free tuition is automatically better than any other.

But on that argument, the review could have recommended the complete annihilation of all living cost support in Scotland and it would still be proposing the “best” system. Clearly (I hope) no-one would believe that.

So we need to get past playing the absence of tuition fee debt as a trump card. It’s something to include in the equation – but how that equation works out, not least across different incomes, then needs working through.

It’s also worth noting that the full comment was “taken together our recommendations amount to the best student support package that would be available in the UK” (emphasis added). It’s a small point, perhaps, but fee support is specifically outside the review remit. It was not allowed to make recommendations about fees. Thus the source’s own words invite us to compare living cost support packages quite specifically. So it’s a particularly bold claim, in any world where £9,000 is higher than £8,100.

Over the past year, the Scottsh government has been very keen to celebrate its decision to increase the income up to which it provides maximum grant. It was doing so again yesterday:

The Scottish Government said almost 3,000 additional students qualified for a non-repayable bursary or saw their funding increase as a result of the income threshold being raised from £17,000 to £19,000 last year.

I’ve been critical of this line, because it obscures that the celebrated increase simply reverses most of cut made by the same people in 2013. Up to 2012-13, maximum grant was available at household incomes below £19,300. In 2013-14 that was cut to £17,000. Even leaving aside that £19,300 in 2012-13 would now be somewhere above £20,000, the most recent increase isn’t therefore much to boast about. It’s like standing hard on someone’s foot and then expecting them to be grateful when after a while you stand on it a bit less hard.

The reason for highlighting this is not just as a failure of honesty in government communications (though that is partof it), but because the change in 2013 had such a serious negative impact on individuals. As the line quoted above shows, for the first time we can now say with some certainty how many.

The way the figures have been presented (nothing dubious, just how it’s been done) have made it impossible to identify until now how many people fell into the £17,000-£19,300 band. This year, however, we have figures on the numbers with incomes up to £19,000 and we can compare that with earlier years, when the cut-off was lower.

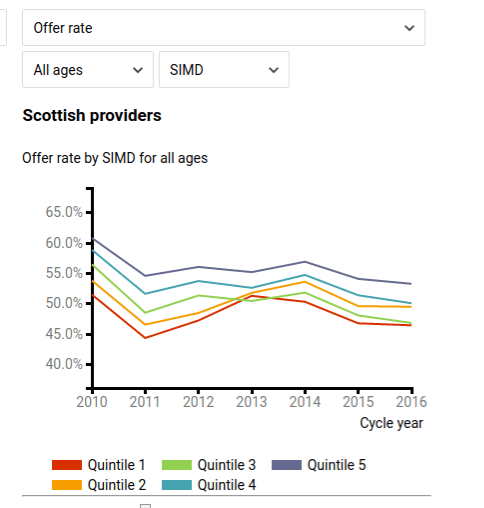

The chart here shows how numbers in the lower and higher bands have changed: the higher band was £17,000 to £23,999 for the first three years and £19,000 to £23,999 last year.

There were a pretty consistent 9,000 in this band between 2013-14 and 2015-16. The lower band fluctuates more, which is probably because it contains a large majority of low-income mature students, whose numbers have tended to be quite unstable.

On the basis of these numbers, the SG’s 3,000 looks like a fair estimate of the number caught by the threshold cut in 2013-14 (or a bit of an under-estimate, bearing in mind the new limit is still below the old one). The changes, down and up, have been applied to everyone, new and continuing. The original move probably saved the Scottish government around £4m a year in 2013-14 and 2014-15, and slightly less in 2015-16, when £125 was added to the grant reducing the saving by around 10%.

Here’s why the impact of the 2013 change on the group can properly be described as brutal.

Other data suggest it is likely most of those affected were younger students, eligible for YSB. In 2012-13, every young student with a household income up to £19,300 was entitled to a grant of £2,640. If they chose, they could top that up with loan of £3,740 to a total sum of £6,380 (living away from home; less loan was available to those living at home).

In 2013-14, their grant was cut to £1,000 and they were offered a loan of £5,750 (whether living at home or away), to bring total support to £6,750. Thus they lost £1,640 of non-repayable cash funding every year. Even if they were willing to take on the whole higher loan, and borrow £2,000 more a year, that only improved their overall support by £400.

Around a quarter of YSB takers don’t borrow: those in this group simply lost 62% of their income. Remember, this included students already in the system, who’d entered expecting this grant.

I think a real injustice was done to the people in this group, who experienced a clear, significant detriment. In regarding this as an acceptable penalty to apply to this small, vulnerable group, government did an archetypally bad bit of policy-making. In throwing its whole weight uncritically behind the 2013 changes (at the time: they no longer do) and not even insisting on a safety net for those already studying, NUS Scotland performed poorly.

Thus, every time ministers highlight the increase in the threshold in 2016-17, they are doing so on the back of these dramatic losses for two or three thousand young people from low-income homes every year from 2013-14 to 2015-16. I’d not be so proud of that.

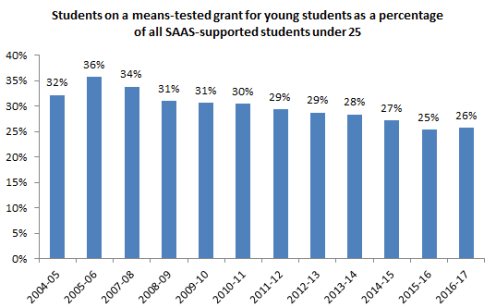

Some brief analysis of the annual Scottish student support statistics are published today: link here.

Last year, it was the accelerating fall in the numbers getting a means-tested grant which stood out: see here: https://adventuresinevidence.com/2016/10/26/the-mystery-of-scotlands-disappearing-low-income-students/

This year numbers are higher, but the absolute number on Young Student Bursary and, even more, the number on YSB as a proportion of young students remains historically low and needs an explanation.

Means-tested grant claimants

Something really odd has happened to the number of younger students claiming a means-tested grant.

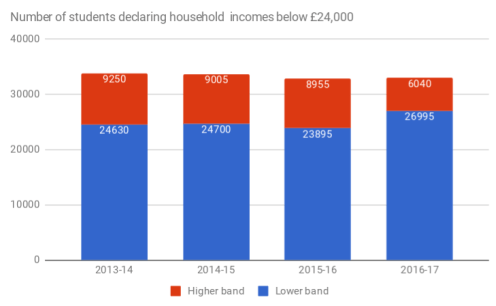

The figure below shows the trend in the number of students claiming YSB (plus the separate Young Student Outside Scotland Bursary from 2004-05 to 2010): YSB is available to students under 25. The figure will understate the number of young students getting a means-tested grant prior to 2013-14: various small non-age specific means-tested grants existed prior to that, which were rolled into YSB (and Independent Student Bursary, for older students) at that point.

Note: Rise in 2005-06 likely to be due to increased rates and thresholds that year.

While the numbers below the age of 25 have risen by 21% since 2004-05, the number of young students getting a means-tested grant in the last two years has fallen to its lowest level in over a decade.

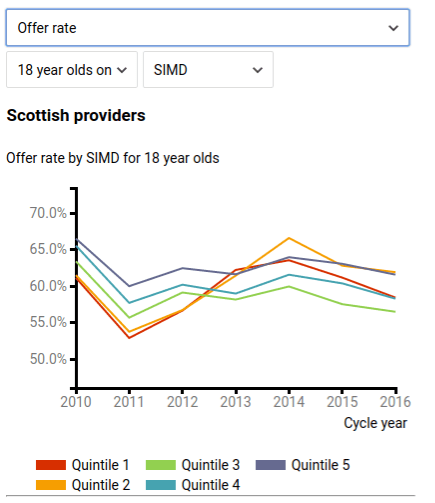

The figure below shows YSB (and YSOSB) recipients as a percentage of all under 25. Some people on YSB may have been over 25, so the true proportion of the relevant age group getting a grant will have been lower in every year – but the trend is startling.

There may be some sort of technical explanation for the fall in the last two years (have some been moved onto the much lower Independent Student Bursary?), but even then the longer-term trend is a concern. It clearly deserves explaining. If the student support review due to publish soon has nothing to say about this, it will be very disappointing.

The news on independent students is better. These have had a national means-tested grant since 2010. After a boost to numbers in 2013-14 (likely to be due to many students moving on to ISB who were previously on a separate grant for professions allied to medicine), the number here had been falling, but is now up. The number of older students over the period has grown, too, but only by 3.8%. The potential for year-on-year volatility looks like the issue here.

Spending on means-tested grants

In 2015-16 £125 was added to YSB for most recipients, and in 2016-17 the income threshold for the maximum grant was put back almost to where it was in cash terms in 2012-13.

The combined effect of these is now visible: between 2014-15 (before either change) and 2016-17, total YSB spending rose by £3.5m (9%), and ISB by £2.7m (23%, reflecting not least the rise in numbers this year) .

Total spending on means-tested grants remained £31m/35% lower than in 2012-13, even so, and these comparisons are in cash terms and take no account of inflation.

The average YSB payment rose from to £1235 to £1391 over the same two-year period. For ISB, the figures are £710 to £827.

Total borrowing

Total borrowing has exceeded £0.5 bn for the first time (we already knew this from an earlier data release by the Student Loans Company).

Average borrowing remains almost unchanged: it is £5,300 compared to £5,290 the year before. The rise in the total is due to more students borrowing.

Debt distribution

Borrowing by income is hardly changed, so that borrowing continues to be skewed towards those at low incomes, as the design of the system would predict. Nothing new here: Scotland’s particular use of student loans remains indefensibly regressive.

Conclusion

These figures contain no major new surprises, other perhaps than the large increase in ISB claimants. But what’s happening to the number of younger students receiving a means-tested grant really does demand attention.

Last week, the Scottish Labour Party highlighted recent cuts to grants with this tweet.

This post checks the £400 quoted and concludes that the real terms fall has been nearly double that (and as much as £899, if looking specifically at Young Student Bursary). As well examining Labour’s claim, the figures here also provide some context for the current review of student funding, which is due to report towards the end of this year.

Sources

The last year before the SNP came into government was 2006-07. Data on student funding over the period is available here: 2015-16 is the latest year for which average payments can be calculated. The relevant data and my calculations from it are here: Grants 2006-2015.

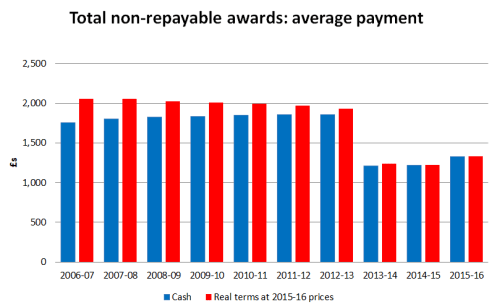

Total non-repayable funding (grants and bursaries)

The £400 looks to be a calculation of the cash value of the change in the average value of all forms of non-repayable SAAS support taken together: this fell from £1,757 to £1,328 (-£429). However, these figures take no account of inflation. Given this comparison covers a decade, it would be more conventional to put figures into a common price base – to make them “real-terms”. At 2015-16 prices, the 2006-07 average would be worth £2,051, making the real terms fall over the decade larger (£-723).

Young Student Bursary

Young Student Bursary

Total awards is a useful figure, but looking at it masks larger falls in the grant targeted specifically on young low income students. For Young Student Bursary, the cash fall was from £1,914 to £1,336 (-£579). The real terms fall is larger. At 2015-16 prices, the average YBS payment was £2,235, so that the real terms fall in the average grant payment to a young student from a low income family was -£899.

As the charts show, the drop is almost all accounted for by the unpublicised cut made to YSB rates in 2013. The slight rise in 2015-16 reflects the addition of £125 to most but not all YSB entitlements.

Total numbers receiving non-repayable support and total spending

For the bigger picture, it’s also worth looking at changes in the total value of payments and number of recipients. The charts below show the real-terms value and number of claimants of (a) total non-repayable awards and (b) YSB alone. This shows that as well as the average falling, so did total spending, as did the number of students receiving non-repayable grants, and YSB alone. Yet total student numbers have risen over the period, and in 2013 a number of smaller grants covering just over 2,500 students were rolled into YSB.

The spike in the total in 2010 is due to mature students being brought back into a national grant scheme (albeit at lower rate than YSB): the fall in 2011 is due largely to the abolition of travel grants the year after.

Here’s my final response to the consultation on student funding, run by the SG’s Student Support Review.

The questions are still quite open ended, although the review is now in its final few weeks: it is due to report in the autumn. Where questions are asked about a specific proposal, a “minimum income guarantee”, what is meant by that is not defined. The SG uses this to mean “the maximum amount of support, available only to those at the lowest incomes”, but the questions make it sound like what’s envisaged is something more like the Welsh plan for a uniform support entitlement, provided in a different mix of grant and loan, depending on income.

It’s not clear whether the review is prepared to argue for increased cash investment in support for low -income students, or is asking its questions in the context of taking a zero-sum approach to non-repayable funding. That matters a great deal. The difference between FE and HE support, in value and legal entitlement, is a critical issue for the review. But it’s had to see how that gets fixed with no new cash.

The concern about this review must be that, having been told that fees are outside its remit, if it is not looking at increased cash investment, it will be tempted to suggest that the SG makes much more use of student loans to plug holes in its living cost support, particularly for those from low incomes and those studying on FE-level courses (there’s some overlap there). In stacking up debt even more disproportionately among those from the lowest incomes, that would be a regressive move.

In theory, however, the review offers the chance to make some improvements, including to reverse some of the worse features of the 2013 changes: not just lower grants but also a lower income threshold for maximum support (only partially corrected last year), the introduction of very sharp stepped reductions in support at particular incomes, and the removal of any extra support for study in London. It is also a chance to sort some longer-standing issues, such as the lower grant offered to independent (mature) students and the relatively poor levels of support available at incomes between £34,000 and around £45,000. There are new things to look at, such as whether students on 1+4, 2+3 or 2+4 models should have a year (or two) of their debt written off, so that the SG is putting its money where its mouth is, in regard to its increased emphasis on college entry to HE as a route to university.

It’s also a chance to remind everyone of the current government’s commitment in its manifesto to increasing the loan repayment threshold to £22,000 (it is currently around £17,500; it is £21,000 in England and in Wales) and reducing the write-off period from 35 years to the 30 years used in the rest of the UK. Although this unqualified manifesto commitment was remitted to the review (not a common move for a single party government so soon after an election), surprisingly perhaps the consultation does not include questions asking specifically about it. It would be the most effective way to help lower-earning graduates, and if the review does not hold the SG to making these changes, it will be very disappointing.

The consultation ran from the end of June to the end of August. That’s less than the SG’s standard 12 weeks, and coincided with the summer break. If the review nevertheless gets a decent number of responses, it will be evidence that a consultation like this has been long overdue. If it doesn’t, then I suspect the timing will turn out to have been a large issue.

Sections in italics below are my responses. I’ve only answered the ones where I felt I had something to say.

——————————————————

1 – Greater alignment of financial support for students across colleges and universities with increased fairness in what all students can access;

Rationale: to create parity for all students whatever the level of study

1.1 Should there be parity in funding levels available to all students, based more on need rather than the level of study?

This is a hard principle not to support. But if it would simply mean spreading the existing cash resources available for those in the greatest need even more thinly, it would be very problematic. Taking already limited support from one low-income group to help another cannot be the right answer.

There is already some evidence (previously shared with the review team) that take-up of grant, particularly the £500 level of YSB, has fallen as grant has reduced in value: it is plausible that some students do not regard it as large enough to justify asking their families to go through means-testing. Cutting existing HE grants further therefore risks not only higher debt or reduced grant support at low incomes, but low income students falling out of means-tested support entirely.

What is meant by “need” also matters here. Underlying expectations of family support (cash and kind) at different ages and stages are especially important. Does a 17 year old studying at school have the same need for state help as a 19 year old from the same household who is entering post-school education? There is a strong argument that post-school level young people need to be supported in having more choice over where they study and live, and that our expectations of direct family support should reduce at that stage. The review could usefully take a view on this.

1.2 How could parity be achieved and how can we maximise the income available to students?

It is very important that grant and loan are not treated as inter-changeable forms of living cost support. Otherwise, it is very likely that those most dependent on state help with living costs will end up either with the most debt (particularly if they do not move directly from school to university) or not taking out their full notional entitlement.

My MSc research (already discussed with the review team) showed that a significant minority of those entitled to YSB do not take out the loan required to top it up to obtain their maximum entitlement to support. Those in college-level HE are particularly likely to be non-borrowers, especially in first year. Any proposals here should take into account the evidence we already have of the lower propensity to borrow of those on sub-degree courses in college. Grant-only HE students receive less support than those who receive an FE bursary.

It is not clear whether the review is prepared to argue for higher investment in non-repayable forms of targeted student support for those from lower incomes. This is however the only way to improve living cost support for those at low incomes which can be relied on to be largely taken up by that group, and which will clearly avoid them facing a later penalty for their lower-income starting point, in terms of having to repay a larger debt.

1.3 How can parity in funding be achieved without having a negative impact on benefits?

I cannot comment on the interaction with benefits, although I would hope the devolution of some benefit powers to the Scottish Parliament would give Ministers more flexibility to deal with the interaction with student support, for example by filling gaps where benefits are withdrawn. I am aware that the interaction with Carers’ Allowance can be particularly difficult for some students.

1.4 What is the most effective way to determine which students are most in need of bursary support?

The Rees Reviews in Wales noted that there was scope to refine the means-test and that some systems include wealth/assets in the assessment.

The system could do more than it currently does to take into account the number of dependents there are in a household and the impact of that on family liquidity. Students from middle and higher income households which are supporting multiple children in post-school education could be given access to an additional loan entitlement, as a de facto way of enabling parents in this situation to spread their contributions to their children over a longer period.

The move in 2013 from tapers to large losses in entitlements at three particular incomes (especially £34,000) should be reviewed: it results in disproportionate loss of support for minor changes in income.

The age discrimination in HE grants should be removed, so that students no longer receive a lower grant (and higher loan) because they are classed as “independent”. The original justification for the different treatment of young and independent students was that independent students had access to a separate Mature Student Bursary Fund and were not liable for the graduate endowment. Neither of these is still true. Mature students are disproportionately from disadvantaged backgrounds, and have historically received additional support in recognition of their great financial liabilities: yet in Scotland at present are expected to borrow more.

2 – A simplification and clarification of the systems used to provide financial support to students in Scotland today;

Rationale: to remove some of the unnecessary complexities and enhance the student experience

2.1 What are the key features of the current system that may deter or make it more difficult for students to access, or stay in college or university?

The heavy reliance on loans for living cost support at lower-incomes risks deterring some students from taking out their full support, increasing the risk of excessive term-time employment and/or dropping out.

The sharp drop in total support available as soon as income reaches £34,000 and relatively low total support to those from households with incomes between this and around £45,000-£50,000 carries the same risk. The total support for those in this income range is unusually low, and therefore the expectation of family contributions unusually high, within the UK. Scotland is also exceptional in the UK in withdrawing all grant support at £34,000. There is a strong case for using grant rather than loan to improve the support for this group.

2.2 Do any of the current rules and/or practices in place make it harder to access or maintain study?

2.3 How could the way in which financial support is delivered to students at college or university be improved?

3 – Better communication of the funding available, including a clear explanation of the repayment terms of student loans;

Rationale: to assist students and prospective students to understand what financial support is available and when and how they access it

3.1 What type of information on funding would be helpful to students – both prospective and continuing?

More information should be available in an easily absorbed form similar to that developed by Sarah Minty of the University of Edinburgh (here).

The SAAS website should be substantially improved, to be more intuitive and more easily navigable between sections. An online calculator, as available for other parts of the UK, should be developed.

3.2 How and where should that information be made available? Would a particular format be more helpful?

Online, paper-based and face to face information all have a role.

3.3 When should potential students first be given information on financial packages of student support?

Young peoples’ concerns about funding as a barrier to future study should be explored early, possibly at the point when N5 subjects choices are being made, to make sure that serious misconceptions aren’t limiting choices. But detail on funding may be better left till later, not least as it can change. Decisions here should be guided by research, or further research should be commissioned, if it does not exist.

3.4 What role should colleges / universities/ schools play in providing information on student support?

They should all have staff able to provide reliable advice on this.

3.5 What more could be done to support parents/guardians to better understand the student support funding available?

This group should be specifically targeted with information, as there is emerging evidence that they are the single largest influence on young people’s understanding of their financial choices.

It is not clear why parental contribution expectations ceased to be published several years ago. Even if there are (legal?) reasons for this decision, some way has to be found to tell parents about their expected contribution, for as long as support decreases as income rises, and to make it clear that this is a very long-standing part of student support in Scotland at middle and high incomes.

3.6 What could be done to help students understand more about student loans, including how and when they are repaid?

Scottish Ministers’ negative rhetoric about student debt, used to make comparisons with other parts of the UK, risks feeding Scottish students’ reluctance to make use of student loans. The Scottish Government needs to consider whether it is sustainable to rely so heavily on student loans for living costs while being so generally critical of student debt elsewhere. The common implication that £27,000 of debt is unreasonable sits uneasily with that being around the amount a low-income student is expected to accumulate in Scotland over 4 years.

The leaflet produced by Sarah Minty, cited above, provides a very good summary of the loan system for students, which could be the basis of information provided in other media.

4 – Further consideration of the levels of funding required for all students and the funding mix.

Rationale: to provide more funding, particularly for students from the most deprived backgrounds, and funding choices for students

4.1 Should a ‘minimum income’ guarantee be introduced across all students?

Does this mean following the Diamond Review model of giving all students access to the same value of support, using a mixture of grant and loan? If so, two considerations are:

first, the more this is provided by loan at low incomes, the more likely it is that a substantial of minority of students will either not benefit in practice or will be relatively disadvantaged long-term by having larger debts (see above);

second, if loans to those at high incomes are made available at the current highly-subsidised interest rate, it is more likely that this cash will be used not for immediate support needs, but to give these students additional long-term advantages, for example by being used as low-cost funding towards buying property, funding unpaid or low-paid internships, or postgraduate study. The Rees Review found evidence of such practices in Wales when interest rates there were pegged to inflation, as here. There is a strong argument that any loan support made available to those at higher incomes for living costs should be provided at a less subsidised interest rate, as a disincentive students from higher incomes using student loans to increase their relative advantage.

4.2 What should the ‘minimum income’ guarantee be, and why? Should it be linked to the Living Wage?

4.3 Under what circumstances should a ‘minimum income’ apply?

A “minimum income” would imply that it is a minimum for everyone. However, that label is currently used in Scotland to mean the value of the maximum support available to those at the lowest incomes, which may be confusing for students.

If this question is intended to explore the income level up to which the maximum value of support should apply, in line with the meaning of the current Scottish MIG, then the current cut off is relatively low, particularly given that support then falls by £750 in a single step. It is lower in cash terms than applied in Scotland in 2012, and therefore now even lower in real terms. It is substantially lower than in England. It is closer to the Welsh and NI level but these systems do not then withdraw support so sharply. There is a strong case for increasing the income threshold for maximum support, especially if a stepped system continues.

4.4 What is the appropriate balance of bursary / loans within a ‘minimum income’?

Bursary should provide the bulk of support for those at lower incomes. It should at least be high enough to mean that they are not expected to rely more heavily on loans than those at higher income, as is currently the case.

4.5 Rather than only Higher Education students, should all students have the option to access student loans, regardless of their level of study at college or university (in addition to existing bursary entitlement)?

The rationale for the introduction of student loans in 1990 was that graduates are likely to have higher earnings from their participation in HE. There is already evidence that this is far less likely to be true for those on HN-level courses. It is very questionable whether this argument can be applied to FE students. Unless the repayment threshold is set much higher, these students would face a significant risk of seeing a net financial loss from taking part in FE, if they take out student loans which they then have to repay.

At a more practical level, as already argued, it is very likely that many FE students would not take out a loan, so that the government might have addressed their living cost support needs on paper, but not in practice.

Loan support for FE is also likely to lead to a much greater accumulation of debt by low income students who later progress into HE, unless such students can have earlier years written off if they progress.

4.6 Are there ways that the terms and conditions attached to student loans ( e.g. interest rate or repayment threshold) could be reviewed to support consideration of extension to all students?

The present government undertook in its manifesto to substantially increase the loan repayment threshold and bring the write-off period into line with the rest of the UK. As Barr et al have shown, these two changes would do the most to protect low earners and thus make the loan scheme more progressive. The review should strongly recommend that these commitments are honoured for all students.

5 – Any other comments, ideas and innovations

5.1 Please use this space to provide any other comments which you believe are relevant to the review. In addition, your ideas and innovative suggestions are welcomed to help inform our final report on how the student support system can be fit for the future.

The decision to remove the additional living cost allowance for those studying in London should be reversed. Scotland is the only UK jurisdiction not to provide such an allowance. Only small numbers are affected: the cost would be small and would come from the loan not the cash budget, if models elsewhere are followed.

Ways to limit the accumulation of additional debt by those at lower incomes in 2+3, 1+4 and 2+4 models of study should be explored, including debt write-offs for repeat years. Although this might reduce the incentive for students to avoid repeat years, (a) these students would still face a penalty of later labour market entry and (b) it would encourage these students to make post-college choices based on their best educational outcome, not on limiting debt. It would also increase the incentive for government to reduce the scale of repeat years.

The review group has not put forward a specific model or set of possible models: the

document instead asks a series of relatively open questions.

The consultation was launched at the end of June, with replies due by the end of this

month. A link to the consultation is here.

Attached is my current draft consultation response. It’s a work in progress, because

I’ve not had time before now to do anything with it. What’s here is my first go, entirely off

the top my my head. I’m posting it in this form now for two reasons. First, in case

it’s at all helpful to others also trying to meet the deadline: I’m conscious that this

consultation has been shorter than the SG’s standard 12 weeks, and that its falling over

the summer will have been tricky for those based in education institutions. Also, I’m

sharing it in case anyone reading it wants to remind me about relevant things I may have

forgotten. But in that case you may also want to put in your own response!

The University of Edinburgh recently announced that it would, for the first time, be offering some places through clearing which would be reserved for students from Scotland from the most disadvantaged areas. It’s an inventive response to the difficulty the university faces (I’m assuming) in getting more applicants from these parts of Scotland.

It made me think about what puts people off applying to certain universities, and something I’ve heard just often enough to think it’s worth some attention. We need to talk about open days.

I think of the relative who visited St Andrews in the 1970s and felt so at odds with who they encountered that they didn’t go (to university at all, in the end). The friend who also went to a St Andrews open day (in the 1980s this time) and had the same reaction, spending four very happy years instead at Strathclyde. Other much more recent anecdotes, from friends and Twitter contacts, about Edinburgh and (less often but also) Glasgow. It seems possible that the experience of visiting certain universities as a potential applicant on a general open day can be specifically off-putting.

I have been around and about George Square in Edinburgh over a couple of recent open days, seeing young people with their parents. Poor things, is my immediate reaction: the choice seems so enormous, so life-determining. I’m happy never to face that again. But I also notice the signs of social class. This is not a very mixed crowd.

There’s some relevant personal history here, too. In 1984, I went to an open day at Oxford. No-one else from my school, an average sort of local comprehensive, was interested, so I did the 5-hour-each-way train trip solo, arriving blurry from an early start in a strange city much bigger than the place I lived, its station on the edge of the centre, pre-Google maps and smart phones. Two colleges were being open that day. At the first, very old and distinguished, I arrived late and stressed: the benches in the lovely medieval dining hall were already full. It felt as though most people there had come in gangs, buses even, from the big public schools of southern England. With their teachers. I did the tour that followed the welcome speech, half of which I’d missed, but it was agony. I felt like a gatecrasher the whole time, awkward and scruffy and excluded. Then I bolted for the other college on my list, a 1970’s concrete thing on the fringes. I remember it was raining hard. They were surprised to be reminded it was still their open day, but dug me out a friendly undergraduate who wandered me round, and dropped in on a couple of friends, who made me a coffee, cracked jokes and were brilliantly normal. My day improved. Maybe Oxford might be alright.

Reader, here’s my confession. Both my parents went to Oxford. It’s where they met and they remembered it with huge affection. Yes, they were first generation university students and entirely dependent on scholarships. But my father was a university professor. He’d been to one of those big public schools (more scholarships). The very old college was his old college. But that open day nearly torpedoed my application to the entire university, because I felt so out of place among the other potential applicants I met there. It certainly took college number one off my list. And yet I was someone whose family background should have put me at the top end of the feeling-entitled-to-be-there scale. So if I felt like that, I wonder where that leaves so many others.

So here’s my modest proposal. People from fee-paying schools should be contained in a separate open day. That’s it. Everyone else should be able to come on the other days without being confronted with that extraordinary, overwhelming wall of outward confidence and upper-middle-classness which can be so daunting and alienating, particularly when you meet it for the first time. Now anxious parents are involved, it must surely, if anything, be worse.

I don’t mean here that there should be special open days for “access students”, but for once applying the thinking of quotas etc to the other end of the spectrum: putting the “difference” badge on someone else for a change. Not because I have anything against any of these young people individually, but because en masse they are so bloody daunting. They can’t help it. They may not even like it. I know now that cultivating that outward air of self-possession is a fundamental part of what private schools do, and that it can conceal plenty of insecurity and confusion. But at 17 that wasn’t at all obvious.

Indeed this could be taken a step further. Some state schools are also conveyor belts to the ancients; maybe they should be separated out too. The criterion could be schools which have sent more than x% of their leavers to ancient or Russell Group universities.

Most access initiatives target the people identified as disadvantaged. We remain less comfortable curtailing the effects of privilege. This proposal indeed barely does that: these young people still get their open day. I suspect it would be regarded as an unacceptable, even so: however radical we say we are willing to be, acknowledging the negative effects of advantage as well as disadvantage remains alien to most policy-making and practice.

Footnote

My mother only made it to university in 1947 because of the new system of scholarships introduced at the end of the second world war. I am literally a product of the post war student funding settlement.

Baby boxes are due to be given out to all new mothers in Scotland who have a due date from 15 August onwards.

There’s not been much coverage of how this is being achieved in practice, but there’s some interesting points to make about that, ahead of the media coverage which can be expected round the launch.

Who is providing the boxes?

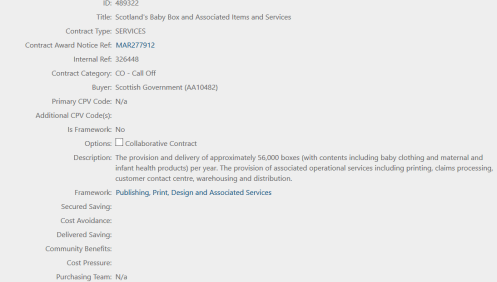

The Times reported back in April that the contract for all aspects of baby boxes – getting the box made, obtaining the contents, filling it, delivering it, dealing with questions about its delivery – had been given to APS Group (Scotland) Ltd. This is a firm which began as a print services company but has developed a more general publishing and marketing brief. This is the main APS website, and here’s details on its Scottish arm. The most recent accounts for the APS parent company mentions its business roots in printing. APS (Scotland) is 75% owned by APS and its last filed accounts recorded a turnover of just over £9m: the baby box contract roughly doubles that.

A print and marketing firm is not perhaps the obvious body to be sourcing and distributing baby care goods to new parents nationwide out of the health budget (see the Level 4 health budget here). But there’s one strong reason for their having this contract.

Since 2014, APS has a “call off” contract with the Scottish Government for “publishing, printing, design and associated services”: here’s a piece from when they first won the contract. The call off contract is a product of the out-sourcing by government (a long time ago) of various publication services. This particular call off contract means that officials don’t have to go looking for a designer/printer every time they produce something – they can just go straight to APS. It’s a very useful arrangement once you no longer have in-house services, and has been around for ages. The call-off contract was won via a competitive tendering process and in fact covers a range of Scottish public sector bodies, not just the SG (more on that here). This is part of a general efficiency drive: the Director of APS Scotland was a guest speaker at a McKay Hannah event in 2014 on managing public sector budgets.

The nature of the contract

A PQ answer to Elaine Smith MSP confirmed that

The [baby box] contract awarded to APS (Scotland) Group Ltd, takes the form of a call-off to the existing Publishing, Print, Design and Associated Services Scottish Government Procurement Framework. This is a single-supplier framework agreement to which APS Group (Scotland) Ltd were appointed in 2014 following an advertised procurement process.

This means no further specific competitive bidding process has been required for the baby box work. There is nonetheless a specific contract for the boxes on the SG site (link). Here’s what it says:

All this means that

The provision and delivery of approximately 56,000 boxes (with contents including baby clothing and maternal and infant health products) per year. The provision of associated operational services including printing, claims processing, customer contact centre, warehousing and distribution.

has been interpreted as falling within “Publishing, Print, Design and Associated Services”.

That’s a surprisingly wide interpretation of those terms. The more detailed coverage, see here includes “promotional goods” and “warehousing and logistics”, which I suppose might have been felt to provide enough cover. Still, procuring and delivering 56,000 large multi-item boxes to new parents is clearly a bit different from producing a few campaign-specific lanyards or pens, and posting out documents. So the decision not to submit this to competitive tendering must surely have to had to be put through the legal wringer, given how it stretches the interpretation of the terms of the existing call-off contract and that it is so large in value, at £35.3m. The legal implications of its size relative to APS Scotland’s existing scale must also presumably have had to be examined (“due diligence” is the fancy term here), as this contract would prima facie raise capacity issues well beyond any explored when the original call off contract was let. This is pretty exceptional stuff, in other words, and worth noticing for that reason.

Costs

The contract formally runs from February 2017 to July 2019, suggesting around 6 months of preparation and then around two years’ worth of supplies boxes, with a “max extension option” of 24 months. The Times established however that the £35.3m cost assigned to the contract covered the whole four years (this has also now been confirmed in a PQ response), up to summer 2021, so it’s not clear how “optional” the extra two years are, or why this wasn’t simply let as a four year contract.

The total implies a cost of £8.8m a year, compared to £6m a year originally quoted and the £7m in the most recent budget (which it becomes clear was only a part-year cost). As the Times piece notes, the SG confirmed it was expecting each box to cost £160, rather than the £100 originally expected. This does mean however that it has managed not to get pulled to something close to the £500 or so which was the cost of the boxes in the pilot.

Answering a further PQ from Elaine Smith MSP on why costs had increased, the Minister said:

We considered the views of parents in determining the contents for the initial national roll-out of boxes.

Consequently, we have included more expensive items, including the digital thermometer and the baby wrap, which parents involved in the pilot have indicated that they found more useful than they originally anticipated. These are the sort of items that some families on low incomes might consider to be unaffordable, yet they are recommended by professionals as being helpful for babies’ wellbeing.

…We will keep the contents and costs of the box under constant review to ensure we continue to achieve effective value for money.

Asked by Monica Lennon MSP how much of the cost was specifically attributable to the box and the mattress (an important point, because doubts are being increasingly raised – not just in Scotland – about claims made about the boxes specifically: it might be a lot cheaper just to give everyone the contents in a jolly bag), the minister declined to provide a split of the costs due to commercial sensitivity.

The case for taking more time

One argument for by-passing a competitive process may have been lack of time. The decision to go straight to a full national scheme this year is because of promises made by Scottish Ministers early on. There are good reasons to argue that a more cautious approach would have been better. Other places are running pilots which cover the whole of the expected period of use, and then allowing time for reflection on the experience before committing further: see here. Scotland is exceptional in making a political commitment to a national scheme, ahead of any piloting. Here, the evaluation was conducted less than 5 months in, and while it was published in June, the contract for national implementation had already been let (without any announcement, as far as I can see) since February.

There was no external reason to rush. Finland has had these boxes since the 1930’s, we are often reminded. Scotland could have taken a little longer to lay the ground for a scheme here. If the politically-set timetable was a significant factor in the decision not to hold a competitive tendering exercise, that would have been another good reason for taking longer. A central purpose of competitive tenders is to help control spending, to protect the public purse (this money is, after all, coming out of the hard-pressed health budget). Instead, we have ended up in the odd position where lots of effort has gone into running a competition for the design on the box, but none at all into one to choose the particular commercial supplier handling £35m of public cash.

A competition will be run next year, according to this PQ answer.

Due to the imminent procurement exercise for year 2 of Scotland’s Baby Box, the itemised value/cost of any item is currently commercially sensitive. Once that exercise is concluded, we will review the efficacy and sensitivity of providing itemised costs and if appropriate, provide further information in due course.

As the SG has already done its bit by letting the main contract, this appears to be for the contents only, and it’s not clear whether this competition will be run directly by the SG, or on its behalf by APS Scotland, as the main contract holders (though I’m not sure how public procurement works if done at arm’s length by a commercial body).

Practicalities for parents

The SG has a website for new parents which has more about the arrangements for distributing baby boxes, with detailed Q&A about the practicalities which anyone following this might find useful. The involvement of health professionals is limited – midwives are asked to fill in a registration card with mothers at around 20-24 weeks and send that off. APS makes delivery arrangements direct with parents thereafter, on an Amazon-like model. Anecdotally, just in the last 2 days I’ve come across a couple of examples where women well past 24 weeks haven’t yet heard anything from their midwife about this, so it’s possible coverage may be a bit patchy to start with. APS must be providing the forms, but it’s not clear who is responsible more generally for making sure all midwives are briefed and engaging with pregnant women.

Conclusion

Shortly there’s going to be a whole lot more PR about these boxes. So it makes sense at this point to stop to ask which organisation is actually running the project in practice, and is therefore immediately accountable for the practical side, and how they were chosen.

For me, this all feels like further evidence that it would have been better to approach this idea with much more caution. That would have permitted more time to reflect on the pilot and do a proper cost-benefit analysis of this against other ways achieving particular aims with the same money (indeed, clarifying what those aims are, and the balance between them: SIDS reduction, symbolic gesture of welcome, practical support?). It’s now also clear that standing up to the political impulse to go national, fast, would have enabled the costs to be pinned down better before the long-term commitment was made, and also allowed time for the government to run a proper competitive tendering process for any national scheme, thus avoiding the need for any special interpretation of the contracting rules.

Footnote 1

Ironic note. The managing director of APS (Scotland) is also the registered director of a firm of funeral directors, and so now literally provides cradle to grave services.

Footnote 2

I have a lot of sympathy with this piece from April in the BMJ by a Scottish GP: “The best health interventions may come without gift wrapping”.

Footnote 3

There’s been a lot of coverage today of an intervention by a cot death charity, the Lullaby Trust, on baby boxes. It’s not specifically aimed at Scotland but adds to general concerns about claims made by box suppliers about a link with reduced cot death. It echoes concerns expressed by others, which I picked up in this (warning: very long) piece a while back. On a technical point raised by the Trust about baby boxes in general, it’s worth saying that the SG Minister has said that the Scottish box does have specific formal safety accreditation. But the Trust’s global unease about the claims over cot death still stand.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Suzanne Zeedyk, who asked me earlier in the week if I knew anything about the tendering process and set me off looking for all this, and to various others (none in government or the parliament, I feel I should add, to prevent anyone from having an unnecessarily bad day) who I subsequently contacted and helped me find various things linked here.

A less complete version of this first appeared on my site late yesterday, before I had seen all the various things quoted here,

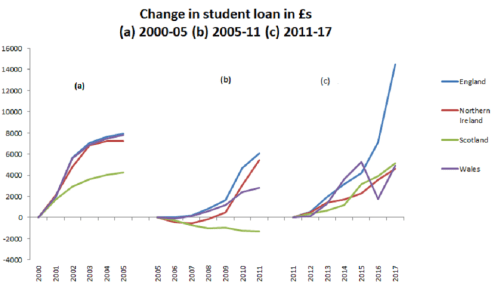

Scottish students tend to leave higher education with lower levels of debt than those elsewhere in the UK. Some of that will be due to the higher proportion of people here who only stay in the system for one or two years (mainly HNC/D students). Some of it may be down to a higher proportion living at home. But policy divergence has also evidently been a large part of the story.

Differences in debt are sometimes presented as specifically an achievement of the past decade, but the figures below suggest it’s been a function of devolution more generally.

The changing picture on final debt across the UK

Using this week’s figures on final student loan from the SLC, it’s possible to chart how debt has changed in Scotland over the past 17 years. It turns out to be a tale in three parts: rise, fall and rise again. It’s also possible to unpick exactly how levels of student debt in Scotland have diverged from those in the other UK nations

Disclosure: I was working as a civil servant on policy in this area between 2000 and 2004, specifically the implementation of the graduate endowment and Young Student Bursary. Readers will want to be aware of my background in reading this.

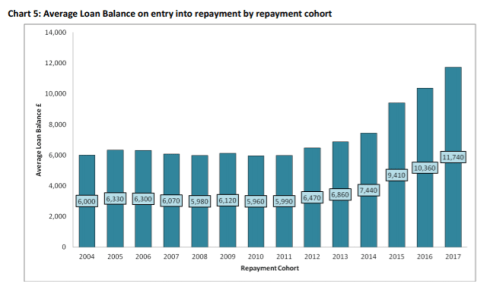

This chart shows the average final debt of students as they entered repayment in each year from 2000. There’s a time lag, so for example the 2017 figures relate largely to those who left HE in 2016. If they completed a degree, they will have entered no later than 2013.

The divergence between Scotland and other UK nations set in quickly after devolution in 1999.

It’s possible to identify three distinct phases in student loan change in Scotland. First there was a phase where debt rose, then one where it fell or barely changed, and one last one where it rose again.

The chart below shows the annual change in debt each year in each nation, separating into the rise/fall/rise periods for Scotland. 2000 is the earliest year covered by the recent SLC data.

2000-05

From 2000 to 2005 final loan in Scotland rose each year. In the early years most students leaving had studied under pre-devolution arrangements. As time passed, more leavers had been under the “Cubie” arrangements brought in for new entrants in 2001 by the Labour/Liberal Democrat coalition. This

- reintroduced a grant for younger students called Young Student Bursary (grants were abolished UK wide just before devolution)

- abolished a means-tested annual upfront fee of £1,000

- introduced a single post-graduation payment (of around £3000 at current prices) for around half of students (in effect young students on courses of degree length: HNC/D students and all mature students were exempt).

- reduced the amount of maintenance loan available to those from higher income families.

The first one-year HNC students under these rules appear in the chart above in 2003, HNDs in 2004, 3 year degree students in 2005 and 4 year students not until 2006.

Over 2000-05 Scotland peels quickly away from the position in the rest of the UK, finishing at about half the debt level. Debt in the other UK nations rose much more sharply between 2001 and 2003, before leveling off. At this stage, all three other nations are very similar: Wales and Northern Ireland were following the English model (Wales didn’t have powers to deviate, Northern Ireland had other pressing concerns).

2005-2011

Having begun to flatten out by 2005, average final debt levels in Scotland then fell every year until 2011 (except in 2009, when they rose very slightly). In 2005, 2006 and 2007, those entering repayment were graduates of the Labour/Liberal Democrat scheme (or in a few cases, one of the pre-devolution ones). Grants had also been increased in 2005, reducing debt.

In 2008, those entering repayment benefited from the incoming SNP administration’s abolition of the graduate endowment in 2007. Debt continued on its the falling trend (other than the modest rise in 2009) up to 2011.

Over the same period debt in the other UK nations pulled away further, particularly in England and Northern Ireland, which both moved to a higher £3,000 fees (plus grant) system for new entrants from 2006. Most of these entered repayment in 2010. By 2009, the use of new powers in Wales shows in its less quickly rising line (grants were increased and fees limited).

The abolition of the graduate endowment contributed to a continuing downward trend in Scotland. However, the effect wasn’t enormous: average final debt fell by just under £600 (-8%) between 2007 and 2011. Most of the increased difference between Scotland and the UK by 2011 is accounted for by the decision by the Labour/Liberal Democrat coalition in Scotland in 2004 not to adopt the new £3,000 fee model brought in in England in 2006.

2011-2017

From 2011, final loan increased every year in Scotland. A finding that I hadn’t expected is that it rose by almost exactly the same absolute value in all three devolved nations (£5,150 in Scotland, £4,590 in Northern Ireland and £4,915 in Wales, though quite erratically). Only England, adopting a £9,000 fee for new entrants from 2012 broke away.

The rise here was due to the Scottish Government increasingly turning to loans to fund living costs, particularly after 2013, when substituted loan for one-third of grant and generally increased total loan entitlements.

How did loan end up so much lower in Scotland?

These charts unpick the process by which average loan in Scotland has departed from the levels elsewhere in the UK. It becomes clear that it has happened in these stages:

- active policy-making by the Labour/Liberal Democrat coalition – introducing the Cubie package – accounts for Scotland having around half the average debt of the the rest of the UK by 2005.

- passive policy making by the Labour/Liberal Democrat coalition – declining to follow the example in England, Northern Ireland and Wales of £3,000 fees – accounts for a further widening of the gap after 2009.

- active policy making by the SNP administration – abolishing the graduate endowment – has some effect but much less than the others here.

- passive policy making by the SNP administration – declining to follow the example in England of £9,000 fees – has a large effect on the difference with England, but none with that for Wales and Northern Ireland.

The difference in final debt levels is generally claimed as an example of the success of the current government in Scotland. However, it becomes clear that much of that difference is due to the position it inherited from previous administrations and that its own active contribution to that difference is a relatively small part of the story.

Its most substantial contribution to differences in debt has been not to follow the £9,000 regime in England. This is a wholly devolved area and no political party or civic Scotland body in Scotland has advocated this model, at least in public. So the main challenge facing the government in not following England has been in finding ways to pass to other parts of the budget any negative impact through Barnett of reduced spending on English universities. (It’s not clear how large a task this has been, however, as the SG is keen not place a cost of free tuition, some of the money saved in England may have been re-spent on other devolved areas, and no savings elsewhere have been specifically attributed to tuition fee policy).

Put briefly, these comparisons bring out that the difference in debt levels between Scotland and the other devolved nations is largely an achievement of governments elected in Scotland prior to 2007, and that the current government’s contribution to the difference with England is largely down to a decision not to use devolved powers to do something no-one here has ever asked it to do.

Footnote

Figures underlying the graphs here UK debt for blog

The Student Loans Company has published the average final debt for students who left HE last year: link here.

The figure for Scotland is now £11,740, an increase of 13.3% on the previous year. The longer term trend is more striking: see chart below. Average final debt has roughly doubled in cash terms (the real terms rise will be less dramatic, but still substantial) since the current Scottish Government entered office in 2007 promising students that it would “dump the debt”.

Source: SLC

The rise since 2012 is due to the changes to student funding implemented in Scotland in 2013 still working their way through. What’s pushing up debt is the substitution of loan for around one-third of grant, and the general use of loan to increase living cost support across the board, but especially at middle-to-high incomes. There’s potential for a further step up next year, when the first cohort on four year courses who have studied wholly under the 2013 reforms will be included.

The figure for Scotland remains lower than elsewhere in the UK. That’s partly due to there being no fee debt for those staying here, but the size of the gap with other UK nations is exaggerated by the higher proportion here who leave after doing a one or two year HNC/D. That will bring down the average. Roughly, it appears to mean that the Scottish average doesn’t represent the average after 4 years (let alone the 1+4/2+3/2+4 models used by half of those moving from college to university). It’s closer to the average over 3 years.

The next nearest UK nations for debt levels are Wales (£19,280) and Northern Ireland (£20,990). With its £9,000 fee regime pretty much fully rolled out, England now sits £32,220: this figure will rise further, given grant cuts for new entrants from last autumun, but that won’t show until this group leaves in a few years’ time.

In comparing Scotland and Wales, in particular, it’s worth remembering that in Scotland low-income students borrow above average each year, while in Wales the opposite applies.

So there are a few reasons these figures don’t provide a good guide to the reality of final debt for low-income students leaving university in Scotland, or comparing with other parts of the UK. That won’t stop them being quoted in support of the Scottish status quo. But their limits shouldn’t be forgotten.

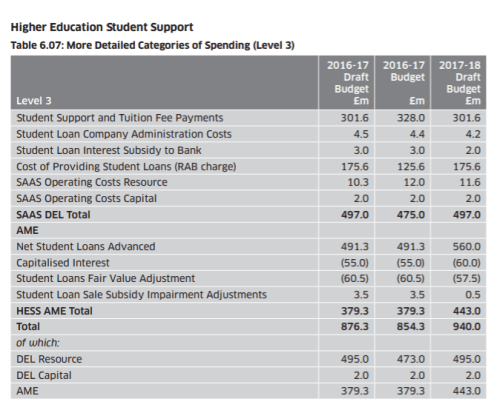

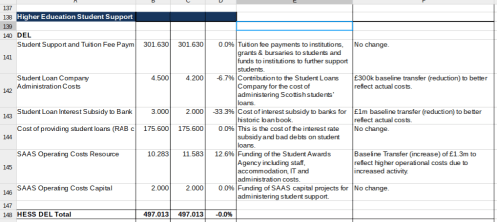

This post summarises the current position on grants and loans for full-time students in higher education in Scotland, and the background to it.

Background

(i) Fees and other payments

The Scottish Government funds the whole tuition cost for almost all first-time, full-time Scottish and EU students in Scotland, from the government’s cash budget. Therefore no-one from any background has to borrow for part or all of their fees. Scottish students will only need a fee loan (as students in other parts of the UK get, to defer fee payments) if they go to study elsewhere in the UK.

Between 2001 and 2006, young students entering degree-level HE full-time were liable to pay the graduate endowment, a single payment of £2,000 at 2001-01 prices, after finishing university. The income from the GE was in theory ring-fenced for student bursaries. Graduates could either pay it in cash or add the liability to their existing student loan (or take out a first-ever loan) to defer the payment. Because of exemptions for HNC/D students, including those on “2+2” models, mature students, disabled students and single parents, slightly under half of all the full-time students the SG supported were liable to pay the GE, which was bringing in around £23m p.a. by 2007 (more here). When the current Scottish Government says it brought in free tuition, it is referring to its abolition of the endowment in 2007. It is also often, in practice, describing its decision not to use devolved powers to copy either of the fee regimes which have applied in England since 2007.

(ii) Living cost grants

Scotland has relatively low student maintenance grants (here called bursaries). Most living cost support is offered instead as student loan.

Between 2010 and 2012 inclusive, the means-tested grant for younger students, Young Student Bursary, was frozen in cash terms (see here for more on how its value changed from 2001 onwards). In 2013, the Scottish Government cut its total spending on maintenance grants by around £35m, or one-third. The maximum YSB was reduced from £2,640 to £1,750, and it was withdrawn more quickly as income rose. The government lowered the income at which maximum YSB was payable from £19,300 to £16,999. Many students lost £900 a year and some much more. The Scottish Government argued they could make up the difference by borrowing to fill the gap. Older students get the lower-rate Independent Student Bursary. This was introduced as a lower-rate grant by the Scottish Government in 2010, and then also scaled back in 2013.

In 2015, the Scottish Government added £125 back on to some grants, costing it around £5m, and in 2016 it reversed most of the cut to the threshold for maximum grant, raising it to £18,999 (likely to have cost it a bit under £2m a year).

The current system

The resulting living cost model in 2016-17 is in the table below.

| Young | Independent (ie mature) | |||

| Bursary | Loan | Bursary | Loan | |

| 0-18,999 | 1,875 | 5,750 | 875 | 6,750 |

| 19,000-23,999 | 1,125 | 5,750 | – | 6,750 |

| 24,000-33,9999 | 500 | 5,750 | – | 6,250 |

| 34,000 plus | – | 4,750 | – | 4,750 |

A particular feature of this model is that it is built round those from the lowest incomes, especially mature students, taking out the highest loans. Until grants were abolished in England in 2016, Scotland was the only part of the UK taking this approach. It means that someone at a low income who wishes to take out their full entitlement to living cost support over four years faces a debt of £23,000 plus interest if they are younger, and £27,000 plus interest if they are older. Grants are higher in Wales and Northern Ireland (where students also only have to borrow for the first £3,900 of their fees: true for Welsh students anywhere in the UK, for NI ones in NI).

Actual borrowing

Figures on annual borrowing by income are published annually by the Student Awards Agency Scotland (SAAS). The latest are here (see Table A6). They show that Scottish students borrowed a total of £0.5bn in 2015-16.

Around 70% of Scottish students take out a loan in any given year, and almost all those who borrow, borrow the whole amount they can.

The table below is adapted from the official statistics. I’ve added two columns. One shows average borrowing across the group as a whole, i.e. including borrowers and non-borrowers. The other shows the percentage who don’t borrow in each income group. It’s reasonable to assume from other research that there are more non-borrowers in the higher income group because students’ access to family resources tends to rise as family income increases. It is likely that even within this group, non-borrowers are more prevalent at higher incomes: it is quite plausible that at, say £60,000+, non-borrowers are in the majority.

The net effect of lower income students having higher loan amounts and making more use of loans is that students in the highest income range borrowed in practice around half as much per head (around £3,000) as those in the lowest income band (over £6,000). Another way to look at this is that Groups 1 to 4 below accounted for only 43% of all students, but took out 54% of all debt.

Borrowing by income band 2015-16

| Total students | Borrowers | Average borrowing (active borrowers) | Average borrowing (all) | % Non-borrowers | ||

| 1 | No income details: receiving max bursary | 10,055 | 9,360 | 6,660 | 6,201 | 7% |

| 2 | Up to £16,999 | 23,895 | 19,105 | 5,890 | 4,711 | 20% |

| 3 | £17,000 to £23,999 | 8,955 | 7,220 | 5,760 | 4,648 | 19% |

| 4 | £24,000 to £33,999 | 8,980 | 7,265 | 5,610 | 4,542 | 19% |

| 5 | £34,000 and above | 2,965 | 1,850 | 4,650 | 2,901 | 38% |

| 6 | No income details: receiving no bursary | 70,010 | 46,830 | 4,650 | 3,112 | 33% |

Note: I’ve removed EU students (14,705) from the figure for total students, as these students can’t borrow. I have assumed that they were contained in Group 6, as very few can claim means-tested support. That may not be exactly right, but it should be near enough. Most students with an income over £34,000 will be in Group 6, which covers those who chose not to submit income details, generally because they are above the threshold for bursary. Group 1 by contrast will be those who had no relevant income to declare and got the highest bursary level. Group 5 is a small group whose income details SAAS knows, although they are over the bursary threshold. I have excluded here a very small group of low-income students separately shown in the SAAS table who anomalously have no income but don’t get full bursary: there’s something odd going on with this group (it may be that many don’t complete a full year).

Caution: final borrowing

Separate figures are published each year for students’ final borrowing. The most recent Scottish figure is £10,500. These figures are widely quoted but have to be handled with care. The average will be brought down by the large number of students in Scotland on one or two year courses, and – as shown above – any average will conceal variation by income. More on that here.

Conclusion

The Scottish system is not debt-free in the absence of fees: indeed Scottish students are borrowing a substantial amount as a group each year. The Scottish approach relies heavily on loans to cover the state’s role in providing low-income students, in particular, with living cost support. Grants are now so low that those from the lowest incomes are taking on the most of that living cost debt. Equally, at high incomes, many students will be borrowing nothing.

Defending existing policy in Scotland means defending this outcome.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

It seems common to assume that we’re faced with a straight choice on tuition fees, where the state either funds the whole of everyone’s tuition costs, or all students have to take out a loan for £9,250 a year. It’s a perspective stuck in a binary choice between whatever-we-do-now-in-Scotland and whatever-they-do-now-in-England. Other options are of course available. That’s what this post is about.

A starting point

The simplest alternatives for fees are:

- setting the fee level at some number more than zero, but less than £9,250;

- means-testing fees; or

- some combination of these two.

There’s a fairly common argument that any move away from free tuition inevitably means Scotland would end up where England is: the slippery slope perspective. That puzzles me, because we would only end up there if that was what the politicians we elected chose. It seems to assume we can trust them to keep it free, but not to maintain any alternative position. On this thinking, tuition fees are an addictive drug, from which governments must be kept away at all costs. I’ll come back to that at the end.